Who in the world are those people? Everyone talks about them. We are wondering who they are. It certainly couldn't be us.

It started very simply. A colleague came to our graduate class to discuss culture. She asked us to empty purses and wallets to see what could be learned about each student's culture. It was amazing how much we learned about the social, political, and cultural institutions which represent the various cultures among the group. Before she left, the professor explained to us that there are many definitions of cultures, but essentially they all have two commonalties: cultures are learned, and they are shared.

When she left, I spontaneously shared with the class some of the things I could remember learning from my own culture. When I left home to attend college, I met my future husband. I remember our initial conversation because he told me several things about himself that bothered me. I remember the discomfort I felt when I learned he was from Iowa. I was from South Dakota, and you know how those people from Iowa are. He added to my anguish when he said that he was from a farm. I was from a ranch, and you know how those farmers are. He further told me that his family belonged to the Farmers' Union. Horrors! My family belonged to the Farm Bureau, and you know how those Farmers' Union people are. I didn't ask any more questions because I was afraid of what he might say about his home culture. However, I very clearly remember wondering what his politics and religion were. You know how those Democrats and Catholics are!

The class and I laughed about the things which I had learned from my own culture: ranchers were good, and farmers were bad; Republicans were good, and Democrats were bad; Protestants were good, and Catholics were bad. As we were laughing together, a young grad student slowly raised her hand and shared her culture with the class.

"I went to private Catholic school for 12 years," Heather shared with the class.

"And, you know how those private school kids are," one of her friends said which relieved the tension we were feeling. The class and I nervously laughed.

"Do you know who I learned to hate when I was in private school all those years?" she asked us.

"No," we answered curiously.

"Public school kids and teachers," she quietly and seriously told us.

"That's us," someone blurted out.

"You know how those public school kids and teachers are," another student offered weakly.

A third student responded to my initial comments, "And it wasn't the Democrats who were bad either. It was the Republicans. I learned they were only interested in making the rich, richer; and the poor, poorer.

This sudden outburst about Protestants vs. Catholics and Democrats vs. Republicans made the class and I realize that we were on a slippery slope. We were entering new territory. It was exciting and dangerous -- ripe with potential and disaster. This was not a part of our prescribed curriculum; this was not on the syllabus. I was not transmitting knowledge; we were generating ideas together; we sensed transformation could not be far behind. However, the truth is that we raced up that learning curve with reckless abandon. Everyone wanted to share; we all wanted to learn. This conversation of our lived experiences mattered to us. It was real. For the remaining six weeks of the semester, we wrote, read, reflected on the "other" which was new and disturbing language for many in the class. Not every moment was wonderful. But, in the end, we all learned far more than was on the original syllabus.

What is the other? It is all I haven't experienced. It is what I don't know and understand. It is the upside-down to my right-side-up. For each of us, the other is unique. My other need not be yours. However, many of us are often uncomfortable with the other. The antithesis does not affirm. The other asks us questions, and our answers don't fit (Wink, 1997, p.5). |

The purpose of this article is to share with those who are interested in multicultural education how one group of graduate students discovered in very clear terms who the "other" was for them.

Let the Dialogue Begin

Within the first 20 minutes of this spontaneous and powerful class dialogue, I noticed tears in the eyes of one particular grad student, Susan, who was sitting beside Constance, who was very, very quiet. As the class continued to share, I noticed that the five students at this table were listening to all the comments, but were only sharing privately. Soon, I saw more tears in the eyes of the other students at this table. Susan is White; she learned to hate Blacks. Constance is Black; she learned to hate Whites.

As the evening wore on, all the students in the class became aware of the intense pain of these five students. The rest of the class demonstrated their empathy and respect by leaving this small group alone. Finally, the tension was broken when someone referred to the small group as "the crying table." Somehow, it made it okay for tears and laughter to be a part of meaningful teaching and learning about multicultural education. After this comment, Susan told the whole group that as each of them had shared who those people were, she suddenly realized that she had been taught to hate each group which had been named. In retrospect, we believe that this painfully honest moment was the impetus for further dialogue and this article. Later in the evening, I sat down to visit with this group of five tearful students.

"Constance, you are the only African-American student in class, and you did not share with the whole group." Constance quietly nodded in agreement.

"Why?" I asked.

Silence.

"Constance," I continued quietly, "you were taught to hate me, weren't you?" Constance quietly nodded in agreement.

"I couldn't say it to the whole class," she told me, "because you are all European-American, Mexican-American, and Asian-American. Before this time, I had only thought of it as a Black and White issue. However, now that I think about it, I can see that I never learned to hate White people, but I was taught not to confront them. I had many White friends and knew that they were not much different from me, but the actions of the schools always taught me that we weren't equal. In high school, I often felt uncomfortable because I was usually the only Black person in class. We had tracking, and most of my Black friends were not tracked into the college prep classes. I remember reading Shakespeare in high school, and the teacher was discussing stage make-up.

"If you don't wear make-up, the lights will turn your skin the color of Constances' skin," he told the class.

"I remember exactly how I felt: humiliated, angry, and intimidated," Constance quietly shared with us. Her experiences this Shakespeare class triggered a discussion of, not only race, but also privilege and class. Constance struggled to share with her colleagues how she understood that by being placed in that class, she was assigned privilege; she knew that this social status had not been given to many of her other Black friends.

The Dialogue Continues: The Perspective Grows

I could see that our conversation was centered on North American experiences, although students from many parts of the world were in this graduate class. In an effort to broaden the discussion to a more international perspective, I purposely called on a Hmong-American young woman, Mimi, who asked that her name be changed for this article. It started so simply, but when she finished sharing her story with us, we all had a greater respect for the learning and sharing within all cultures.

"Mimi, who are those people in your family?" I asked.

"The Vietnamese," she quietly and firmly told us.

"You know how those Vietnamese are," a student interjected into the conversation. A few nervous laughs followed.

"Mimi, what would have happened in your family if you had married a Vietnamese young man?" I asked.

She looked at me in complete disbelief and replied, "I never considered marrying a Vietnamese. Why would I do that?" More nervous giggles emerged in the room. Finally, she hesitantly shared that one of her relatives is planning to marry a young Vietnamese and that it is a seriously problem for both families. We noticed that it seemed safe to talk about those people who lived on another continent. But, it had not been safe when we were talking about those people in our own communities. Nor, was Mimi feeling very safe at this moment. The class and I tried to validate her feelings by sharing a list of all the people we weren't supposed to marry.

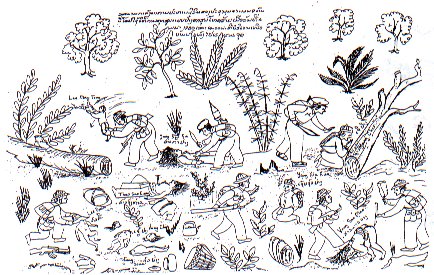

Mimi eventually taught us with the story of her life. She quietly and painfully shared the atrocities of her childhood with her own memories and the following sketches (Hamilton-Merritt, 1993).

Figure A is a documented, eye-witness account of the soldiers killing a Hmong farm family. The women were raped and then killed. The father was killed. The children were pounded to death in the rice mortar.

Figure B is a documented account which took place in 1980 as the soldiers killed and tortured the families as seen in the sketch. We have included only a portion of all that Mimi taught us about history and hate.

The class ended in silence after learning of Mimi's cultural history. We decided we would each go home and reflect and write about what we had learned from our own childhood culture, and we would share it next week. Several of the students shared with their families and rediscovered their past together. This is the story of our continued cultural learning and sharing, and our surprising discoveries.

The Dialogue Takes Us Back to Our Year Books

On our journey to discover who those people were, we started to examine hate, fear, and distrust. We began by talking about when we were young. In small groups, we reflected on our own experiences and reactions to those people. As we did this, we realized that our old yearbooks would be a great place to begin the painful process of critically reflecting on some of our previously-held assumptions.

When the semester began, none of us ever thought that our old high school yearbooks would become part of the curriculum. However, that is exactly what happened. When we took time to reflect critically , we were surprised to see what we learned.

It started very simply. Carolyn came to class with her high school year book, circa 1970, to share with her colleagues. Just as Susan's honest emotions had triggered the first phase of the dialogue, so now the faces in the yearbook served as a catalyst for an intense discussion about ethnic diversity within specific geographical locations and time frames. The areas represented at this small group were rural and urban California, Arkansas, and Idaho. Some yearbooks were as white as snow, while others were filled with the colors of diversity.

"One third of my graduate class was Black," Carolyn reflected with her colleagues. "Now, why do I remember that number after all these years? I know there were many Asian-Americans and Latino-Americans, too."

"My high school was all White, and the Blacks all went to another public school. I just never thought of it," said the young man from Arkansas. "My high school yearbook was White; the school across town was all Black. I just never gave it a second thought." He eventually flew back to his hometown in another state and discovered that the two public high schools were still very segregated. The White students continued to believe that those people were the Black students in the other high school; and, the Black students continued to believe that those people were the White students in his former high school. The pattern of fear was perpetuated. As he talked, others began to interrupt him with stories of local high schools which are still quite segregated. They had just never thought of it until he told about a school that was far away. The distance brought our own reality into closer view.

The Dialogue about Language: To Hate or Not to Hate

As one small group was reflecting on their past by rediscovering their yearbooks, another small group of graduate students was reflecting on our use of language. We will be honest: We just don't know what verb to use. As we shared and dialogued in class, the students often said: I was taught to hate Black people. I was taught to hate White people. I was taught to hate rich people. I was taught to hate poor people. However, when we wrote the word, hate, it seemed so powerful on paper. This raised another painful question: Is hate more dangerous when it is visible on paper or hidden in the heart?

As we were struggling with our own use of the verb, hate, suddenly another dangerous verb emerged among the students. Hate led us to fear. Several students suddenly added that they were never taught to hate; rather, they learned to fear certain groups.

"My family taught me not to hate, just to fear," one student said.

"I was taught never to use the word, hate. I was taught to classify and dislike people if their beliefs conflicted with the beliefs of my parents," a second student added as his fellow-students grappled with the power of status and social sorting.

"Those people in my family were African-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, and Asian-Americans. My family taught me not to hate, just to fear them, a third student said.

"We feared having to go to school with the normal, under-privileged public," Heather, from the Catholic school experience, added in the dialogue.

Again the class and I sensed the steep learning curve of this dialogue about hate and fear. The word, fear, led us to immigrants.

"I am the perfect example of one the those people who were not taught to hate, but just to fear. I am suddenly realizing that there is no difference. One of my clearest examples comes from my grandfather's open opposition to any type of immigrant. Plain and simple; he hates them. Incidentally, I love him," Carrie shared. "I recently told him that I was going to teach a group of 22 Japanese exchange students for eight weeks. In addition, my sister and I were each going to host one student in our homes."

"I can't believe you girls would have anything to do with them," Grandpa said to me.

"My grandfather blames them for the death of his brother in World War II," Carrie told us.

"It's like Mimi's story," another grad student added. "Now, I understand what the text books mean when they say the social, cultural, and political context affects kids in schools."

"After listening to all of this," Lisa told her classmates, "I realize that I was taught to fear those Mexicans. This all makes me wonder who fears me now. This is frightening to think about because, as you know, I have many Mexican-American students in my first-grade class."

"Oh, no, what if America becomes a land of immigrants?" a student teased us. It felt good to laugh.

The students were amazed at some of their personal and painful reflections about those people. Several students were overwhelmed with their personal reflections.

"If I had to write out all the names of people who I was taught were inferior or dangerous, it would probably include all other races. In fact, it even would include European-Americans if they were those people who had too many children, parked their cars anywhere but the garage, and sent their kids to public schools. We also didn't like those renters; or those people who tried to operate little businesses out of their homes. I didn't know the word, classism, then. Now, I get it."

Who were those people? We finally decided it included almost everyone: Black and White; rich and people; urban and people; men and women. It appears that almost all religious groups fell outside the norm of our class. It was clear that senior citizens were marginalized.

We were horrified to see just how inclusive our list of people to hate had become. It seemed no one was spared. The following student comments demonstrate the broad perspective of those people. We have divided our comments into race, class, gender, and the other.

Race

Class

Gender

Religion

The Other

It started so simply. We thought we would share and learn about cultures. It seemed safe when the visiting professor came to share with us. However, it didn't always feel safe and simple as we critically confronted our old assumptions about those people? Our reflections caused some of us to struggle with our old ideas, beliefs, assumptions, and stereotypes which were learned while growing up. It was painful when we came to understand that fear is very much like hate, and that much of our hate is covert, and not overt. Many adults in this class grew up believing they were the norm; the standard. All other groups were measured as different from them. By realizing that we are not the norm -- we are all different to someone -- we can respect difference in others and in ourselves. This has been the story of what happened to us when we learned and shared about ourselves. We cried. We laughed. We ached. We cringed. We talked. We reflected. We wrote. We learned. A lot.

During these weeks in class, we finally came to a point where we could agree that hope helps, and hate hurts. We also learned:

At the end of the semester, we attempted to bring some form of closure to our readings and discussions with this article which we wrote during those last six weeks of class. I continue to see these students, and they consistently affirm that their experience with multicultural education continues to be a transforming experience. Carlos Cortés often begins his presentations on multicultural education with a quote from Rudyard Kipling. It was great to quietly share his poem, We and They, to end our semester. The following two lines made us laugh at ourselves again.

"All the people like Us are We, |

The purpose of this article was to share with multicultural educators how one graduate class discovered the other. So, the painfully critical question I now have to ask myself is: How has this changed my classes this semester? The truth: not a bit. This semester I am teaching the class again and struggling to move beyond the melting pot. Any mention of mosaic makes them mad. If, at this point, I were to move into a discussion of the other, I am not sure I could quell the rebellion. My own personal critical self reflection leads me back to one of the very best: Dewey. Accept students where they are! Just as public school teachers cannot write lesson plans for one year in advance, I cannot impose a previous experience on students who are not ready for it. At this point in the semester, I can see that this group of students likes knowing about transformative education, but they don't like living it. However, we professors of multicultural education are very much like farmers; we plant seeds; we plow; we fertilize; we cultivate. Who knows what we might one day discover.

References

This article was written in the last six weeks of the spring semester of 1996 by the professor, Joan Wink, and the students enrolled in EDML 5400: Theory of Multilingual Education. The names of the contributing students are: Allene Beck, Carolyn Caporgno, Samantha Ericksen, Lisa Fasel, Susan Glectcher, Hope Hansen, Patrick Helms, Katherine Hill, Margaret Lima, Carrie Martin, Barbara Mesa, Heather Morganson, Kelly Pinheiro, Liza Runkel, Rosalva Salcedo, Constance Sharpe, Dennis Simpson, Susan Thompson, Mai Vang, Marcia Vineyard, Diana Wildenberg, and James Witter. We wish to thank the reviewers of this article who continued to push us along our learning curve.