Excerpt from: Wink, J., & Putney, L. (2002, pp. 112-114). A Vision of Vygotsky, Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon

Children at Play

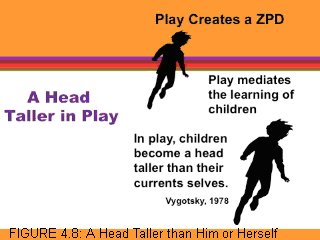

Vygotsky (1978) stated that “play creates a zone of proximal development of the child. In play a child always behaves beyond his average age, above his daily behavior; in play it is as though he were a head taller than himself” (p. 102).

After seeing this graphic, a bilingual teacher shared with us an example of her child at play. This teacher was learning sign language in order to communicate with her four-year-old son, Martín, who is hearing impaired. She and her husband watched in fascination as their son sat on the floor in the family room, signing to himself. Even though he was the only one in the room, he definitely appeared to be conversing with someone else. “When a child’s activity consists entirely of play, it is accompanied by extensive soliloquizing (Vygotsky, 1986, p. 55). The only difference in Martín’s case is that he is not soliloquizing by using his voice; he is signing his meaning. In the mother’s words, “We watched him with amusement because he appeared to be teaching someone, and he was going a mile a minute, totally in his own little world.”

Children at play are in a zone of proximal development. In play, children are acting out real-life situations in which they develop rules that move them beyond their current level. As Vygotsky (1978) stated, “It is incorrect to conceive of play as activity without purpose…creating an imaginary situation can be regarded as a means of developing abstract thought” (p. 103). We have all seen children pretending to be their parents. They act in the manner that the parents would act, sometimes responding with the very words they have heard their parents use.

Play mediates the learning of children, and through play, children develop abstract thought. Mediate means that in play, children reach beyond their real selves as they take on the roles of the characters they choose to be, and take action appropriate to the behavioral rules that govern those roles. Vygotsky (1978) further compared play to the focus of a magnifying glass, explaining that “play contains all developmental tendencies in a condensed form and is itself a major source of development” (p. 102). During play children are reaching out and extending beyond what they are now, while they are projecting themselves. It is as if when children are in a “let’s play” mode, the very act of pretending makes it safe for them to reach beyond their actual level to more advanced levels. The imaginary play world enables kids to reach beyond themselves.

Play creates the zone for children.

Performances of Knowing

The importance of play can be seen in the school setting among older students as well. Shirley Brice Heath (1993) recounted a study of the value of play in the lives of inner city youth. The research involved ethnographic studies of language use among the young people during their extracurricular activities involving various types of youth organizations in three major US cities. These students studied English in ESL classes in secondary school during the day, then participated in a variety of neighborhood youth centers staffed with bilingual adults. The activities in which they were involved at the centers ranged from organized sports to role playing to actual drama troupes in which the young people wrote, produced, and staged their own productions.

In the study, the young people interviewed felt that at school they were getting by in English, but merely speaking and writing words in their classes did not allow them the opportunity to demonstrate what they really knew. That opportunity arose when they became involved in the work of playing at the youth centers. During their activities, these same students who felt that their English was just okay, were demonstrating high levels of English competence. In their roles during play, they discovered a level of competence not found in their day to day command of language. They were reaching to that higher level of performance before competence. We can imagine Harste, Woodward and Burke (1984) reading this and saying, “They were scampering to outgrow their current selves” (p. 135).

The significance for educators is evident in the way Heath (1993) described the phenomenon: The power of role shifting, of framing themselves in play, and of using the new voices acquired through becoming actors seemed to loosen a host of abilities undiscovered in the ordinary run of classroom requests for displays of knowledge rather than full performances of knowing (p. 181).

Assessment and ZPD

The difference, then, between what children can do with assistance and what they can later do alone is a measure of the developing psychological functions. This notion takes into account individual differences. It also focuses upon the communicative nature of learning in which the participants come to an understanding of the operations they are performing.

It is important to note that Vygotsky conceptualized this notion in reference to two educational problems: how children are assessed, and the evaluation of instructional practices (Wertsch, 1985). His concern was that, if we only assess the matured functions, what has been learned, we would miss the possibilities that lie just ahead, in the very next level of performance. This is a notion that even in current times is seen as the distinction between Soviet and U.S. educational research.

Wertsch (1985) cites a discussion in which Leont’ev noted: “American researchers are constantly seeking to discover how the child came to be what he is; we in the USSR are striving to discover not how the child came to be what he is, but how he can become what he not yet is” (p.67). As Leont’ev describes it, US educators look to the actual development level, while USSR educators look toward children’s potential development.