Freire: The Foundation

Let me introduce you to the Paulo Freire I love. I have a tiny tape recorder that often can be found on my windowsill above the kitchen sink. When I begin to lack courage, or when I need more patience, I play only one tape: Paulo Freire (1993).

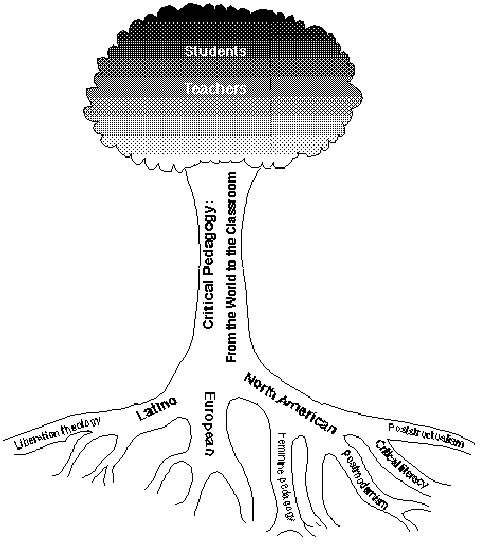

Figure 3.1 Critical Roots

This is a recording I made of him speaking to several thousands of people in southern California but, when I listen to this tape, I still feel as if he were speaking only to me. During this presentation, he spoke of two concepts: teaching and learning. As I listened, the seeds for this book were planted. As we were walking away, Dawn said, “Mom, he’s just like Gandhi, only with clothes on.”

For me, he is the quintessential teacher and learner. Freire has taught many things to many people all over the world. When I read his words, when I hear his words, I learn and relearn to focus on teaching and learning that is rigorous and joyful (Freire, 1994; Gadotti, 1994).

Much of multicultural critical pedagogy in North America today stands on the shoulders of this giant: Paulo Freire. He taught me the difference between “reading the word and the world.” During the 1960s, Freire conducted a national literacy campaign in Brazil for which he eventually was jailed and exiled from his own country. He not only taught the peasants to read, he taught them to understand the reasons for their oppressed condition. The sounds, letters, and words from the world of his adult learners were integrated and codified. Ideas, words, and feelings joined together to generate a powerful literacy that was based on the learners’ lived experiences. The Brazilian peasants learned to read the words rapidly because they had already read the world, and their world was the foundation for reading the words. Traditionally, literacy has been the process of reading only the word. Emancipatory literacy is reading the world. Freire was not jailed and exiled because he taught peasants to “read the word,” but because he taught the subordinate class to critically read the world (Freire & Macedo, 1987). Freire taught the peasants to use their knowledge and their literacy to examine and reexamine the surrounding power structures of the dominant society.

Freire teaches that no education is politically neutral. Traditionally, teachers (that would include me) have assumed that we don’t have to bother with politics; teaching is our concern. I see on my resume that one of the first state conference presentations I ever gave was entitled “Teaching, I Love. It’s the Politics, I Hate.” I now think that I was pretty naive, and maybe even elitist, to think that teaching and learning could possibly take place in a vacuum. Every time we choose curriculum, we are making a political decision. What will I teach, and what won’t I teach? The social, cultural, and political implications are great. After reading Freire, a local teacher sent me this E-mail.

| Freire left me with a new insight. I had never thought about the role of passivity. Before, I did not look at passivity as being active. This oxymoron is new to me. I am learning that these contradictions are confounding and enlightening. |

Schools are social; they are filled with real people who live in real communities and have real concerns. People with multiple perspectives send their kids to schools. Teaching and learning are a part of real life, and real life includes politics and people. Schools do not exist on some elevated pure plain of pedagogy away from the political perspectives of people. If two friends sit down for a social visit, politics is a part of it. Paulo Freire recognized this before many others in education. If educators state that they are neutral, then they are on the side of the dominant culture. “Passivity is also a powerful political act,” a student said to me. Teaching is learning.