pp. 95-101

by Joan Wink

Published by Libraries Unlimited/ABCLIO

Copyright © 2018 by Joan Wink

FIRST, A LITTLE HISTORY: 100 YEARS IN A THOUSAND WORDS

Sometimes, it may feel as though we are the first people ever to enter into complex discussions and arguments about what is best for schools; however, this debate has been going on for a very long time. The story can be told from many different perspectives, but I believe that it is instructive to learning in schools with a long lens, which provides a broad, historical overview.

I am saying as you must say, too, that, in order to see where we are going, we not only must remember where we have been, but we must understand where we have been.

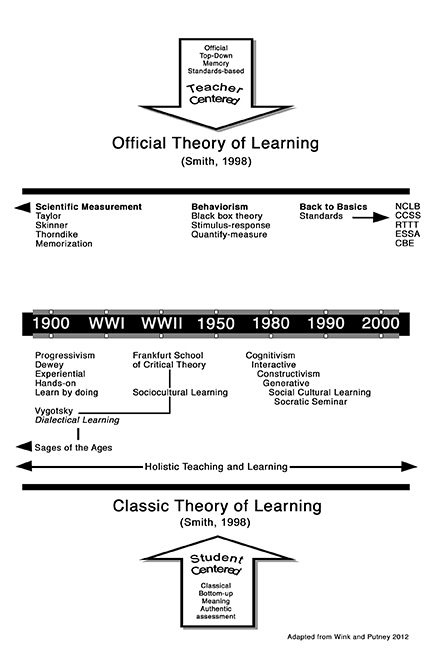

History: So what? Why does understanding history matter in schools? You be the judge. Daily, wherever we go, we hear many different perspectives on teaching and learning. Some of the voices are louder than others. Which one is right? Where did they come from? The answers to some of these questions might be found in understanding history. These questions about what is the best approach for teaching and learning, have been swirling through history for years. It didn’t just begin, as it sometimes feels, when you are living life in schools (see Figure 4.3). The past 100 years plus are particularly instructive when attempting to understand one of the more basic arguments that undergirds the testing-and-standards debate.

I have written about three different perspectives of education: (a) the transmission model, whereby the teacher has the knowledge and gives it to the students; (b) the generative model, whereby the teacher and students construct knowledge together; and (c) the transformative model, where teachers and students not only construct knowledge together, but they take that knowledge outside of the classroom for self- and social transformation (Wink, 2000; Wink & Putney, 2002; Wink & Wink, 2004). However, the purpose of this section is to look at teaching and learning from only two perspectives. Of course, there are not just two or three perspectives, but the following two schools of thought have been experienced by most of us, at one time or another.

First, one point of view concerning teaching and learning is often called skills-centered or teacher-centered. Smith (1998) refers to this as the Official Theory of Learning. It is characterized by the back-to-the-basics movement, scripted reading programs, mandated curriculum, and high-stakes testing. It is based on the assumption that there is one right answer. Memorization matters for its proponents. Lecture and teach/talk are fundamental to this model of teaching and learning. It is driven by extrinsic rewards. Skills-centered pedagogy is the dominant voice of today, and it has been for much of the last century.

The second point of view is often referred to as meaning-centered or student-centered. Smith (1998) refers to this as the Classic Theory of Learning. It is characterized by experiential learning, problem-solving activities, reading a lot of good books, and portfolio assessment. It is based on the assumption that, frequently, there is no one right answer but, rather, multiple perspectives and understandings. Meaning matters for its proponents. Socratic dialogue and problem-solving activities are fundamental to this model of teaching and learning. It is driven by intrinsic rewards. Meaning-centered pedagogy is presently out of favor and has been a minority voice throughout much of the last century.

One problem: These two voices of education are contradictory and simultaneous. It is confusing and frustrating. So, where did these two conflicting perspectives originate?

Between 1850 and 1900, many in the United States were hard at work building a nation. During this time of the Industrial Revolution, railroad construction and the factories were operating under a school of thought that is often referred to as Scientific Management. The belief here was that, to yield high productivity, each worker had to complete one tiny task, repeatedly. Another person completed a different tiny task. Each person was paid according to how many tiny tasks could be completed in a defined period of time. Factories only needed to line up all of these people and keep a close eye on how much each person produced in the tiniest time possible. It worked great in steel factories as the railroads spread throughout the United States.

However, about 1900, the emerging country began to also need schools. The question was: How do we build schools? Two ideas were discussed nationally: Two simultaneous and contradictory ideas.

First, one voice wanted to follow the model of Scientific Management, based on the rationale that it worked with building a nation, therefore, it certainly would work with schools. The second voice, Progressivism, led by John Dewey, espoused the idea of learning from experience and basing teaching on the needs of the students.

The national dialogue continued until about the 1930s, when B. F. Skinner, after conducting his experiments on animals and pigeons, championed the idea of Behaviorism, with its focus on skills, rewards, memorization, discrete-point tests, time on tasks, and error correction. He believed that human behavior could be controlled by controlling the environment. In schools, Scientific Management morphed into Behaviorism. Behaviorism won the day and most of the past century in U.S. schools. Progressivism did not completely vanish, but it was marginalized. Our national rationale appears to have been that it worked with steel and pigeons, so certainly it will work with kids. Smith (1998) quips that we backed the wrong horse.

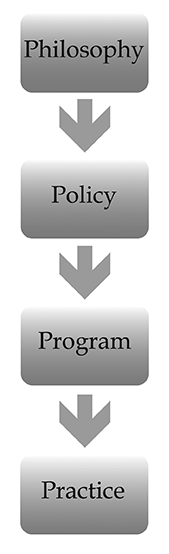

The reason these philosophies matter is because they morph into the Big Ideas, which inform schools. These philosophies eventually get into in our long-held assumptions about beliefs about what works or doesn’t work in schools. Eventually, these philosophies turn into federal and state policies; and the policies become programs, and it changes into practices in classrooms. The problem is that often times, the people making the policies, know nothing about philosophies.

What does this mean in schools today? Is one perspective right and one perspective wrong? No. No, one way works all of the time for all of us. However, most of us are social learners; we like to talk with our friends. Most of us are holistic; we like to see a picture of the whole puzzle before trying to put the pieces together. I am particularly a holistic, interactive, social learner. I like to make meaning. I have memorized a lot of facts throughout the years and remember very few. And, it doesn’t seem to matter. I like to understand. And, this does seem to matter in life.

However, sometimes, meaning-centered pedagogy does not work for me, and I must start with all of the little pieces and slowly build them up. For example, knitting. I’m learning to knit. I go stitch by stitch. Simply knit, knit, knit—I never venture into knit, pearl, knit, pearl. And, then when I complete a scarf, I must learn all over again HOW to get it off the needle. I memorized it once before, but it’s gone by the time I finish a scarf. Knitting has no real meaning for me; I just do it. It is a safe guess to say that I’ll never be a great knitter.

A second example of when I needed to use Behaviorist methods was when I learned statistics. I had to focus on teeny, tiny parts, and I had to MEMORIZE for the tests. Assigning meaning to statistics did not work for me.

One last example, a French class I took as an undergrad. We took a test 4 days a week; I memorized every night, and I got good grades. Do I know French today? No. However, at the same time, I took Spanish classes. We were noisy; we talked; we laughed; we sang. ¿Hablo español? Sí.

Behaviorism was King of Pedagogy for most of the 1930s to the 1980s, when things began to shift. First, we heard of cognitivism. We teachers were encouraged to get the kids to think. I vividly recall telling the high school students in my class in Arizona that we could stop memorizing and start thinking. We cheered. During the 1980s and into the 1990s, many perspectives flowed from cognitivism: interactionist, transactionist, constructivist, constructionist, holistic and social learning, sociocultural learning, critical pedagogy, transformative education, and emancipatory pedagogy. All of these perspectives focused on meaning, meaning, meaning in a social context. They all assumed that we need to engage with our learning and with each other in order to understand. The public perceives that these are brand-new and even radical ideas. The public believes that we need to cling to behaviorism because that is the way we have always done it, or at least for the past 100 years in the U.S. Skill-centered pedagogy has its roots firmly planted in behaviorism, which is an outgrowth of the Scientific Management movement, which was grounded in the Industrial Revolution.

In addition, where did meaning-centered pedagogy come from; or what are the historical roots of constructive, holistic, social-cultural teaching and learning? This model of teaching and learning is influenced by the Critical Theory of Europe in the 1940s and in the U.S. notion of Progressivism of the early parts of the 1900s. But, then, where did Progressivism come from? Progressivism grew from social-cultural teaching and learning espoused by Vygotsky in Russia in the last part of the 1800s; it grew from the works of Socrates, thus Socratic dialogue, in which the teacher encourages the learner to think deeply and independently.

Today, we are locked in a painful debate between two approaches to education. The historical roots of education help us understand why we do what we do. Memorizing history will not help; understanding history will shed light on these questions.

The dominant pedagogy, the skills-centered approach, is perceived to be better because it is what we have always done. Yes, for only 100 years in the U.S. However, the Sages of the Ages gave us a much longer tradition of meaning-centered teaching and learning.

It helps to understand history. I choose Socrates over Skinner almost every day.

Adapted from Wink and Putney, 20212