Dear WinkWorld Readers,

On we go to chapter five, Of Immigrants and Imagination.

First, an mage that chapter, which Katie Knox created for me. Thanks, Katie. Enjoy Japan.

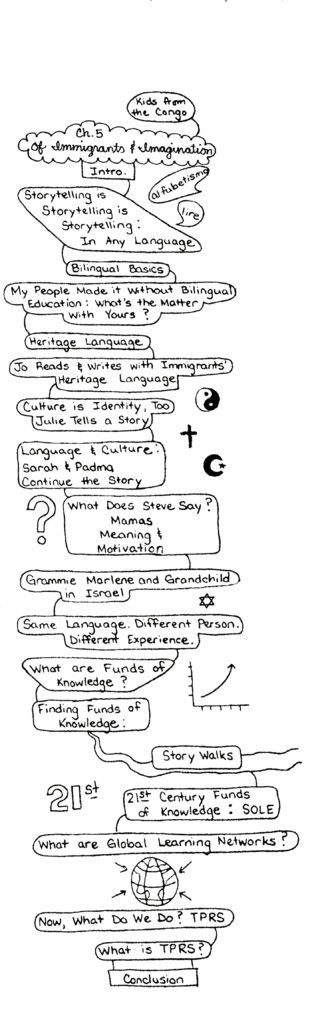

Next a story map (visual Table of Contents), which Missy Urbaniak created for me. Thanks, Missy.

And, finally a selected sample story from this chapter–yes, from the pre-copy edit version. Just faster this way for me. In this section of the chapter, I have bee writing about identity texts and providing different examples.

And, finally a selected sample story from this chapter–yes, from the pre-copy edit version. Just faster this way for me. In this section of the chapter, I have bee writing about identity texts and providing different examples.

What are identity texts?

An identity text is any text (written, spoken, visual, musical, dramatic or any combination), which is laden with the identity or lived experiences of a student—specifically an immigrant student. In an identity text, a student situates his own life in the story. The life of the student is the story. The text itself functions as a mirror, reflecting the identity of that student’s life. We often think of identity texts with languages, which are not used by the school, nor the community. Often times, these languages are not valued, and this can also apply to the speakers of these other languages. Cummins has found that identity affirmation is the key to literacy engagement (Cummins, J., et al., 2005, 2006, 2009). Much more about this can be found in my 4th edition of Critical Pedagogy: Notes from the Real World, which is available on the first page of joanwink.com

***

Yes, this following example is from a school in South Dakota.

Jo, an instructor of young adult immigrants and refugees has collected identity texts for years. The young adult students in this program primarily come from Nepal, Burma, Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan (Darfur), Bhutan, Rwanda, Burundi, Central America, and Congo, although other countries are also represented—for example, I have met Philippine students, and also I met one Chinese student, who was left behind in China when his parents immigrated to the U.S. so they could have more children. He finally made it here alone. When I visit this classroom, I marvel at the strength, good humor, and resilience of people. In addition, I always need to run to a world map to visualize these countries.

This classroom is filled with identity texts: The students share, and they celebrate each other. Jo celebrates; Jo affirms each identity. I stand in awe. The students write or tell their story first, in either their mother tongue or their new language, English. The languages used might be Karen, Poe Karen, Sgaw Karen, Malay, Burmese, Cantonese, Tagalog, Arabic, French, Swahili, Arabic, or one of many tribal dialects. The first language scaffolds the meaning to the next language, English. The use of the first language in the story accelerates the acquisition of English. Eventually, each identity text is told and written in English, although I must admit an absolute fascination with the opportunity to see the identity texts written in the many other languages. At each step in the process, the classroom is filled with honor and celebration.

In what follows are several examples of short excerpts, which I have taken from their identity texts. Once again, I am not using their real names.

Sammy entitles his, “I Fled from Burma,” and he adds the following:

Note to the reader: The Karen people of Burma are victims of an ethnic cleansing campaign by the military government of Myanmar. Therefore, they do not use the name Myanmar for their country, and continue to call that country Burma.

In 2002 when I was 12 years old, I was helping my father at the farm, and my mother hurried to us. She said, “A group of armed military men is looking for the children; they want child soldiers, and they want every child they see. Take this money and go to Thailand.” I told her that I didn’t know where Thailand was, and she told me to follow the group of villagers.

I looked at my mother, and she was crying. I walked away and found the villagers. I never saw my mom again. On the way to Bangkok, we walked day and night and slept a little in the forest. Once 28 of us found a ride in an enclosed truck; I thought I would suffocate. We finally made it, and I found a job in construction, and 8 months later I tried to flee to Malaysia, where I had a brother. I was caught at the border and put in prison. After 8 days, I was able to buy my way out of prison and made it to Malaysia. I could not get a job, until I learned Cantonese. In 2010, I came to America, and now I am learning English.

Kay writes,

I was a street child in Nepal, and I slept on the streets, even though I did not have a shawl to be warm. I am writing this story because I feel sad. My mother left me alone when I was five years old and killed herself. My step-father sold me to a place to work. I ran away from there. My uncle finally found me and took me home. Now that I am in America, I have a heart for the street children and want to do what I can to help them.

Note to WinkWorld readers: I marvel at how well these young people write in English, and yes, they also write their identity texts in their home language.